By Agnes Balazsi

I would like to share my experience of being a researcher and a local in the same time in the same project. Personally, I am a convinced environmentalist, therefore this blog entry is highly influenced by this perspective. From scientific point of view, the ‘’data’’ should be interpreted in complex and neutral manner, even in this post. Yet, being a researcher does not free us of emotional influences or personal backgrounds.

Since I was young, I have dreamt about doing something memorable for my community. Research was one of the options. Due to the Leverage Points project and the Transylvanian case study in it, one of my dreams came true.

Two opposite viewpoints have emerged in me – being the researcher and the local. The structured, specialized and scientific approach necessary for data analysis and the implicated personal experience mixed with the memories of my childhood.

I come from Filia, a village in the Inner Eastern Carpathians, surrounded by the South-Harghita Mountains (1558 m), in Transylvania, Romania. The landscape was shaped during centuries by human-nature interactions mostly based on peasant farming and forest exploitations. Filia is no exception of the changes occurring in rural landscapes in Romania in the last decade. Our research is trying to answer how landscape changes influence human-nature connectedness.

Filia surrounded by its farming landscape

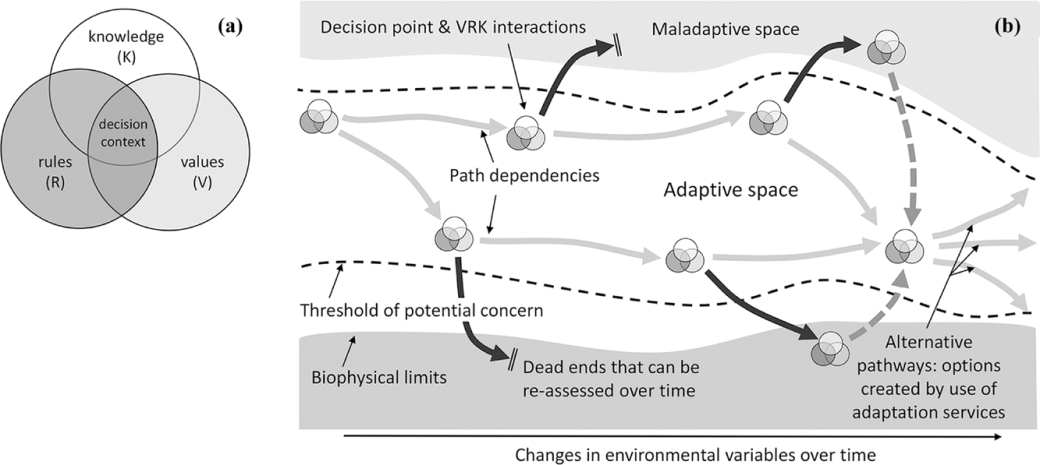

In terms of human nature connectedness, the period after the World War I and the beginning of socialism in Romania (1918-1947) could be generally illustrated by traditional farming landscapes. The connectedness of the community was strongly determined by their material necessities for survival (e.g. food, wood, water, etc.). Anything that sustained life was valuable and highly appreciated in the context of the dominating paradigms of those times. The patrimony (or intergenerational equity and heritage) as the highest value of families assured complex connectedness over the time. Strong emotional and experiential connections sustained by interaction with nature were prevalent as well (e.g. mowing, hunting, firewood extraction, mushroom collection, etc.). Cognitive connection basically meant observation and experience-based knowledge, overlapped with the inherited knowledge about nature between generations (mostly related to farming systems). It is hard to reconstruct the leading threads behind philosophical connectedness, without the influence of interpretation when we look back in time.

Socialism (1947-1989) came with a series of complex changes, starting with the abolition of peasant farming systems, industrialization and development of each economic sector. Rural areas became highly marginalized. The way in which nature was valued changed as paradigms changed, everything was measured in money and its potential of production. Changes in the farming structures led to the functional disconnection of community from the landscape they lived in, and in a deeper sense to the loss of sense of patrimony, property and roots. Industry (coal mining in this area) and services (restaurants, shops) offered at the beginning the feeling of access to well-being and a flowering socialism. However, material connection suffered important changes throughout shifts in the value system: anything able to produce income became valuable. People needed money to have access to food and resources (firewood) on their own heritage. Emotional and experiential connections were limited by forbidden access to state property (forests, collective farms, state farms). Experiencing nature as a way of relaxation became more meaningful once holidays, excursions, sports became accessible for the community. Cognitive connection changed as well, discipline-oriented paradigms started to become dominant over the holistic local knowledge systems. Philosophical connection was infiltrated by the paradigms of socialistic and capitalistic ways of interpreting nature and its resources.

Once socialism fell, the collective farms were destroyed (1990). People reoccupied their land as it was before communism (small-scale parcels), even if formal ownership restitution took longer (or still is not finished). The livestock was distributed between the former members of collective farms and the people tried to continue small-scale agriculture. At the beginning of democracy everything “remained a bit without law” as people said. After 40 years of limitation to own resources people felt entitled to take revenge, using their reclaimed resources to make money (e.g. selling or renting the land, selling the wood). Traditional faming and forestry could not anymore sustain their survival in a modern capitalistic system. Thus, the size of farms increased, while the number of people in agriculture decreased. Due to mechanization the presence of humans in the landscape slowly disappeared. Profit oriented forest exploitation companies appeared, on the remnants of former state companies. Those who were not interested in farming or forestry (or just disconnected through generations) migrated for better living standards to urban areas or emigrated periodically.

Filia is catching up to be a modern society today, despite of its isolated position between the mountain ranges. EU pre-accession and membership came with positive and negative changes. Access to funds favored the development of infrastructure, better environmental regulation and employment abroad. The success of implementation of the CAP and environmental policy at local level is highly disputable. One reason is the quality of the national implementation procedure, and the other is because of local circumstances (e.g. ownership conflicts, wildlife conflicts, marketing of products – incapacity to produce on the EU market, weak environmental awareness). However, landscape functions were preserved due to the continuity of small-medium scale farming (0.5-30 ha). The material connection to nature degraded continuously from previous periods: people getting more and more dependent or interested in imported products of the supermarkets. Emotional and experiential connection became richer again, once limitations were better regulated than in the communist time. Cognitive knowledge has improved because of the access to information and education. Philosophical connection is highly dominated by the environmentalist perspective of valuing nature.

I consider myself lucky, that our playgrounds were the hills, streams, forest and orchards in the surroundings of the village. I especially enjoyed the mowing and haymaking seasons: the smells, the taste of fruits, the sun, the wind, and the rain on my skin. This period meant to me total freedom and security. When I grew up, I physically left the community, but I still belong there in my feelings. Even if I studied agricultural systems and environmental protection, which made me understand the pieces of that “playground”, I sometimes lack the connection with nature that I had. I have never asked our research questions in a scientific way before, but they were asked by the local inside me: “Why did those changes occur?”, “Which are the driving forces that make people act the way they do?”, “Why have things, which were important once, have no more value today?”. I could continue. Basically, changes are not so obvious in the landscape, but the circumstances changed so much, that I am not able to offer a meaningful explanation for myself. As a researcher I am able to understand and analyze the process, but I cannot silence the regrets I feel.

For me, the entire Leverage Points research offered a deep personal process of growing and understanding of changes occurred in Filia.