Ioana Alexandra Dușe

I begin this blog post by saying that Romania is truly amazing, with valuable agricultural landscapes and breath-taking views. Some might say that I am biased, but of course I am; I was born, raised and, for a big part of my life, educated there. However, I see a lot of problems in Romania, in terms of politics (institutional transparency, corruption at the highest level), education, rural to urban migration, environment and sustainability issues. So, the question is why should we pay attention to all of these problems? Well, first it is relevant for us in terms of research, there is a lot of potential for good research to be done in the area. Second, we have to understand the underlying causes of the problems and the symptoms in order to understand how to tackle these issues, and third, because there is no such place like Romania and when one has an opportunity like this, one has to find a way to build on this.

In May, this year, members of the Leverage Points team (Andra, Pim, Nicolas, Chris and I) headed to Transylvania for a week of scoping fieldwork and exploration. Our aim was (1) to see how can we frame our research questions to the Romanian context; (2) to see how can we pursue our objectives considering the complex problems that Transylvania is facing in terms of food and energy systems, and nevertheless we wanted to have a taste of Transylvania (believe it or not, Dracula was not part of the story, this time!) We had 21 meetings with stakeholders from academia, NGOs, local action groups, local government, farmers associations, activist groups, and many others. The amount of information we gained during scoping is very helpful to our future work, a lot of interesting discussions were generated. Here I will just give an overview of the highlight of the meetings, and a few key emerging points.

How are Transylvanians connected to nature?

In Romania, for centuries highly diversified subsistence agriculture and production supported the population. The region of Transylvania still relies on traditional rural land use, often considered ”antiquated” in Central Europe. Farmers in the traditionally managed areas do not use chemicals or intensive machinery, and this has created a large variety of landscape structures, plant communities and habitats for animals. Biodiversity in traditional farming landscapes is also supported through mutual socioecological relationships, in which rural communities influence ecosystems and vice versa. This reciprocal relationship provided strong incentives for sustainable land use, however, the benefits people derive from nature are tight to their value systems and to their connectedness to nature.

Transylvanians perceive, value and interact nature differently. People from the rural areas (who call themselves “peasants”) are very pragmatic and understand nature as more the way through which they benefit from it and appreciate it for livelihoods. Elderly people tend to have a different appreciation for nature, they, have a unique connection to the land, especially compared to younger generations who grow more disconnected from the land/nature. This disconnection is amplified by migration. As more young people leave the rural areas for economic reasons and go to work either in close urban areas in Romania or leave the country, the traditional values related to nature in the region no longer flow from generation to generation to the extent that they did once.

People from urban areas appreciate nature for aesthetics, recreation, and only a small proportion of young people in Romania started developing this feeling of “going back to the roots” for (re)discovering the traditional rural life.

There is another category of people – tourists – who seem to be more aware of the values of the landscape, want to protect it, and appreciate the beauty of the region. These people look for the benefits of the landscape from the natural perspective of the elements. In other words, their connection to nature is oriented towards subtle forms and naturalness.

What are the major sustainability challenges, causes and solutions?

Across Romania, Transylvania included, natural resources have become the object of speculation and massive investments, wherein land owned by millions of Romanian peasants is being grabbed and transformed with far-reaching effects. Some of the foreign visitors have become the famously known “land grabbers”. Data from official registries shows the strong presence of banking institutions and investment funds like Rabobank, Generali or Spearhead International. The range of investors is “exotic” from Austrian Counts, to Romanian oligarchs and Danish and Italian agribusiness companies. Legislation has been driving changes in large-scale monoculture farming, forestry, mining, energy, tourism, and ultimately speculation – as a process that is weakening rural economies and hampering the development of a dynamic rural sector. Urban-rural migration remains a problem along with agricultural intensification, foreign ownership, and the loss of traditional agriculture. Some of the causes are linked to the value systems of the locals and their mind-sets, the level of poor education, unemployment and short term thinking, focused on immediate benefits. Most of the time this shows the lack of hope, pride and support from authorities and responsible institutions.

Energy – seems rather a vague topic for discussion, especially when it comes to renewables and to the support given by the public and by the legislative framework, which is inexistent. People in urban areas still use gas- as the primary energy source whereas people in rural areas rely much on wood.

As for solutions, it will take time to change minds and value systems, and to heal the wounds that history left in Romania after the collapse of the communism. There is still sort of nostalgia floating in the air, but we (as researchers) need to understand what the practical solutions are that trigger sustainability, what are the drivers that shape behaviour, re(create) values for nature appreciation, economic sustainability and legal structures that enable all this to occur.

The role of (in)formal institutions, collaboration and social capital

The informal institutional landscape in Romania seems more and more vibrant. What we witnessed is an outstandingly strong collaboration between public-private actors; local governments and companies/foundations have shared goals and a common vision for a sustainable future. Social capital seems to be the catalyst in this region. In many of our discussions, we came down to the idea of drivers that facilitate mutual beneficial relationships among individuals and collective actions, resulting in longstanding collaborations. So, trust is important and this can be gained and maintained through learning interactions and mutual support. On the other hand, issues such as the legal frameworks, excessive bureaucracy (too complicated, time consuming), and the constant changes to “rules of the game”, are seen as barriers for development. The Romanian Government is pushing on with the development of agro-industry and making substantial efforts to attract foreign investments. The Government’s Program for the period 2013-2016 clearly states it wishes to move towards very large scale, export-oriented agriculture. In Romania, as traditional and organic farmers are being marginalised, land is becoming merely a commodity on which companies can speculate. As some might say, land has become “the new gold”.

One glimmer of hope is the momentum behind participatory groups. NGOs, researchers, some local institutions, and more responsible and active citizens saw the potential in Romania and decided to help to build a more sustainable future by involving the locals and making them proud of what they have. In one of our discussions, someone said something that keeps coming back to me as a good principle in life: “If this should work for me, it should work for somebody else as well”. How this might play out in the Romanian context in the near future remains to be seen.

We had discussions with: Dr. Tibor Hartel, Mihai Eminescu Trust (Caroline Fernolend), Adept Foundation (Ben), Dan Craioveanu, Asociatia Neuerweg (Hans Hedrich), Mioritics (Mihai Dragomir), GAL “Dealurile Tarnavelor”, GAL “Microregiunea Hârtibaciu”, Bunești City Hall, Mayor Saschiz, Asociatia Monumentum (Eugen Vaida), Asociatia CasApold (Sebastian Bethge), BioMoșna (Willy Schuster), Valea Verde Retreat (Jonas and Ulriche Schäfer), Cincșor Guesthouse (Irina Ciungu Suteu), Faculty of Political Science, BBU Cluj (Dr. Gabriel Bădescu, Dr. Cosmin Gabriel Marian and Drd. Mădălina Mocan), Faculty of Biology, BBU Cluj (Dr. Marko Balint), EcoRuralis (Boruss Szocs Attila)

We thank all for their valuable insights and elaborations!

Reference:

Boruss Szocs M.A., Rodrigues Beperet M., Srovnalova A., Land Grabbing in Romania – Fact finding mission Report, EcoRuralis, April, 2015 (online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B_x-9XeYoYkWUWstVFNRZGZadlU/view )

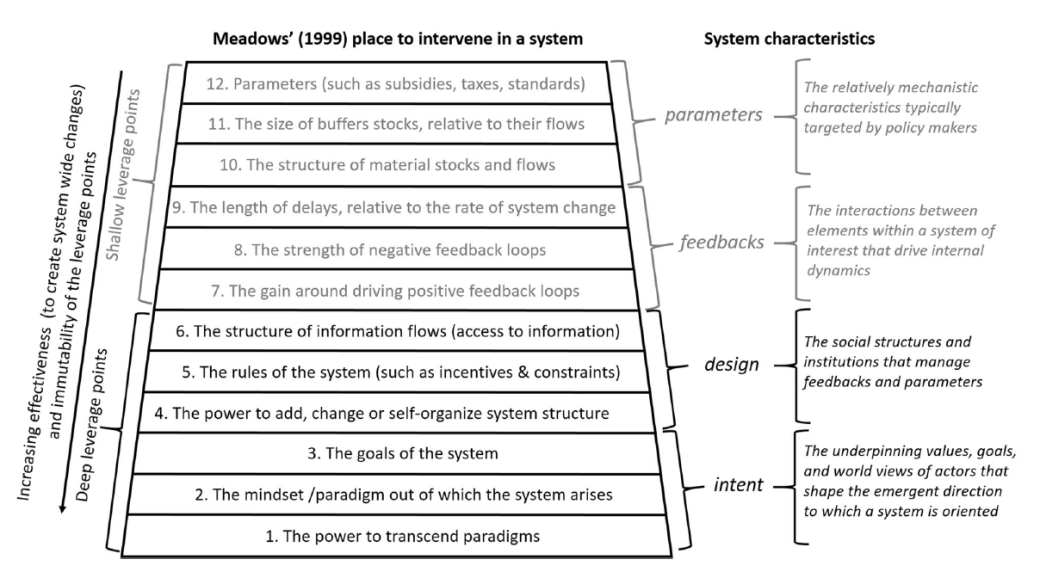

The paper draws on Donella Meadows’ notion of “deep leverage points” – places to intervene in a system where adjustments can make a big difference to the overall outcomes. Arguably, sustainability science desperately needs such leverage points. Despite years of rhetoric on sustainability science bringing about “transformation”, the big picture is still pretty dull: globally at least, there is no indication that we’re starting to turn around the patterns of exponential growth that characterize our era. A potential reason is that much of sustainability science has focused on parameters and feedbacks, rather than system design or “intent” (see above) — when actually, it’s changing a system’s design…

The paper draws on Donella Meadows’ notion of “deep leverage points” – places to intervene in a system where adjustments can make a big difference to the overall outcomes. Arguably, sustainability science desperately needs such leverage points. Despite years of rhetoric on sustainability science bringing about “transformation”, the big picture is still pretty dull: globally at least, there is no indication that we’re starting to turn around the patterns of exponential growth that characterize our era. A potential reason is that much of sustainability science has focused on parameters and feedbacks, rather than system design or “intent” (see above) — when actually, it’s changing a system’s design…